2

Some names lend themselves to the adjectival. Bresson is one. Bressonian just sounds right. Like Shakespearian. Thus, The Bressonian Trouble. Or is it, The Troubling Bressonian?

Can we judge a sensibility by the evidence on the screen? Do we know Bresson by his marking? Or is his point, to some degree, the impossibility of knowing another. A summary of all of his work seems to point to characters who are inexplicable in their actions, in their responses and in the manner they are observed by others. They are not only inexplicable to the viewer but to those they interact with on the screen and this sharing of the observed enigmas of life might be the humanity and power of Bresson’s method.

These notes were made during, and subsequent to, the retrospective of Bresson’s work in February and March of 2020. The series was interrupted before the screening of the last 2 films, which I coincidentally did already have in my possession, so a complete account of his extant films follows. What a perfectly appropriate conclusion to a retrospective of Bresson to find oneself in an inescapable quarantine, doomed to some continuum of isolation with the prospect of the ultimate retribution presented not only by temporal authority but by God and nature. Not that I miss TIFF Bell Lightbox, an airport, antiseptic and corporate, the antithesis of the personalism of Bresson and so concluding these notes at home in my study is much more conducive to a state of mind receptive to Bresson’s spiritual journey. I have kept the films in the order they were shown and for ease’s sake only, the titles remain in English.

Bresson distinguishes theatre as false and cinema in opposition, as distinctly miraculous truth. He elaborates: theatre is enacted on a stage in front of an audience and so is a definitionally false representation of life. By virtue of its existence as “play” “acting”. Cinema as recording, or as he is quick to point out two recordings, one image, one sound – is something else. And that the dominating industry has failed to recognize and embrace this clear fact was an endless source of frustration to him. But it also allowed him to define his work oppositionally and in distinction to the dominant movie form. As a contrarian, particularly in his early films, he was unparalleled. Later, I detect a softening of the “argument” and a more affirming deployment of the elements that he saw as unique to the cinematograph. Any artist’s work is an exercise in rejection as much as application. Paint instead of stone. Michelangelo reveals the characters latent in the stone. Pollack is telling us that intuition knows when to go and when to stop. Pollock looking down at his canvas and not standing in front of it, is fundamental to what his paintings are about.

In the english idiom we have come to understand that there are 2 kinds of moving picture. The “movies” and “cinema”. I’m not sure that in french the distinction is so widely used and as idiomatic, but it was the short hand Bresson used to distinguish his work from the mainstream. He was making cinematographs. The medium is the message. What they are about is what they are about.

The arc of the man’s career becomes most apparent with his later work in colour, as he moved from a defiant contrarian to a more enigmatic but affirming master. The asperity and moralistic tone of his early work evolves into something less certain but richer for its moral ambiguity. What remains constant is deeply felt spiritual revelation in the mundane world. When one looks at his work in the context of the avant garde that was working in parallel in those same years, it seems unfortunate that he was never able to finally abandon prosaic narrative for a more poetic lyricism. He was a believer in the church of cinema, of the auditorium, and he was a believer in the Church. He could never resolve the problem of the individual in the world, the one amongst the many, which is the problem of story; the problem of the creative consciousness. Perhaps it is unresolvable.

It has been said that his work was liturgical, but I see something closer to the Japanese Noh understanding of ritualized work. The actor is a cut-out. The actor is an icon. The actor is a model. A puppet. Interpretation does not figure into it, only transmission.

Diary of A Country Priest begins with the titular diary being opened, but we are not presented immediately with the handwritten words of the priest, but with the blotter markings, chaotic anti-types of ordered narrative. They look nothing so much as like japanese calligraphy or Action-painting.

With Bresson as with others who work in the realm of the poetic and intuition, one must be careful to not over-interpret and yet, on the other hand, to not dismiss too quickly as implausible, devoid of meaning, or as “unintended”, any element in a given work. There is a zone of meaning that is plausible and “verifiable” through a kind of scholarly consensus ( and I don’t mean confined to the academy, but what can be entertained amongst alert discussants ).

With Bresson one must understand that he is deploying elements in a composition. “I want to flee from colour postcards. That’s not what it means, for me, to construct images with my painter’s eye.

Like a painter or any artist choosing one’s media means rejecting others. It is like michelangelo releasing the image from the raw material of the stone.

“ a penetration into the unknown of ourselves”. he states in an interview with Godard.

It isn’t that it is abstracted but that he is using the raw material available to him in a radically honest way. He is not interested in the facile illusions of traditional movies. He is after a different way of engaging with the physical and the metaphysical. Watching Harry Smith’s, Heaven and Earth Magic one sees it done in pursuit of an alchemical conjuring and how that is, in itself, a grand metaphor for the act of creation in cinema. Bresson’s revelation is similar as he makes clear he is after a uniquely cinematic power. His “charms” honour the medium’s power. It is not just a mere structuralist, materialist endeavour. It is an engagement with Mystery using the tools at hand. Smith investigated string figures, quilting, painted easter eggs, not as a “collector” but as an artist trying to come to terms with the divergent ways various peoples with the materials at their disposal, engage with the ineffable, with the inexpressible. Bresson rejected a filmed theatre as a bastard art and went looking for a divergent distillation.

Diary of A Country Priest

seems to be organized around the pairings of type and anti-type as with the blotter and the diary, ink and paper, black and white. The priest’s habit, the high chiaroscuro renderings of scenes, characters appear paired, as the owner of the country manor expresses his sympathy with the country priest, as the young village child from catechism class is paired with the child of the manor owner. The priest is an outsider who even with the best intentions will never be accepted as anything other than an interloper to be viewed with suspicion. The old curé ( himself paired with the young priest ) makes clear, their role is to be respected and obeyed, to keep order, “knowing disorder will win tomorrow, merely because that is the way of the world.”

Even in this earliest of the true Bressonian cinematographs, it is an orchestration of elements and a meditation on the impossibility of coherence, except in the most elemental fashioning of sustenance through the quotidian need for warmth, nourishment, light; even the motorcycle is paired with the otherwise ambulatory priest. The film ends back in the urban world, with a former priest now turned apothecary nursing the dying ember. I need to watch again, but it occurs to me, that the diary as a device is concluded before the curé returns to Lille and that the final image in the diary interstices, is once more the blotter. The return to the city is then told in the 3rd person.

We have too, to understand the films as situated in a time and place, his was an art of the everyday and the now. There are characterizations of alcoholism in the priest’s dependance that are very much of time and place. The introduction of electricity to the parsonage seems like a non-sequitur, almost until we understand that the electrification of the countryside was recent and its announcing the coming of the modern in ancient ways.

A Man Escaped.

The drama of hesitation. Stasis is a failure of volition; while capture is to be bound by circumstance. Sins of omission and sins of commission. Failure to distinguish those oppositions is the tragedy of life. As the film begins, the captive hesitates in his plan of escape, only to be defeated when the opportune moment has passed. Judgement is on trial. It is a drama of hesitation and might be viewed as in dialogue with a contemporary film, Wages of Fear. Freedom comes with a meticulous concern with the mundane and its utility. Pencils are more dangerous than hooks and ropes. Sufficient means. The priest appears to have written his own bible when none was available to him. The story he gives to Fontaine is the one of transfiguration, why must man be born again? To escape. The neighbour in his cell accepting of his imprisonment. The trust Fontaine must have in his cellmate is the final act of affirmation in the choice between stasis and terminal capture or transfiguration and escape.

The motifs that will become more and more parts of the fugue of Bresson’s career really start here, doors half closed, the empty frame pre and post action, the observer who watches through some kind of veil, through peep holes, through windows and bars. We spend our days looking through apertures not even at freedom, but at the closed door opposite our own. Perched on a ledge looking through bars at the abyssal yard below. Queues of men moving along with those in front and those behind. Metonymic parts of men and animals decontextualized, boxed by the picture frame. It would be insightful to produce an index of tropes that are the basis of the rhythm of Bresson. Strip everything else away in an edit that leaves just those elements remaining and the pulsing would be evident, ta tum ta tum ta tum.

Again in Escaped we have the pairings of characters. The respect shown by the German officer for the prisoner. Life under a totalitarian regime would have been the immediate resonance, and again the escape is effected by shimmying across an electrical wire suggests an immediate resonance that is less so now.

Perhaps there is a delusion that comes from photography and his mystical understanding of the force of the image that leads him to believe that what he see is ipso facto what the viewer sees.

The one film we do not have of Bresson’s, although there seems to be an implication that it is extant and held by the estate, is a surrealist short comedy. The film was funded by ? Penrose, a British surrealist and interestingly the father of one of the current generation’s leading mathematicians. It was a debut that is predated by a brief career in advertising as a designer, lithographer and photographer, including work for Coco Chanel. It points to a man who was at the centre of Parisian life in the pre-war years.

Les Anges du Peche

is such a antithetical debut following his time in advertising and as surrealist, that it suggests a conversion experience in the intervening years. Set in a Dominican convent with a cast almost entirely female, it’s preoccupation with ritual, and with the physical detail of life in a convent is the eye of an observer of the manifest. Anne Marie, the protagonist is a noviciate committed to renouncing her materialistic past who become increasingly disruptive and arduous attempting to save a former prisoner, Therese. Finally dismissed from the convent, just as Therese accepts its sanctuary Anne Marie hovers in the woods close by, sneaking onto the grounds at night only to finally collapse from exposure and is returned to the fold to die as Therese takes the Vows to escape arrest. A transmigration. The regimentation, the interest in apertures, the defiant contrarian, these elements will return again and again.

Trial of Joan of Arc

This is the contrarian’s answer to one of the great representations of trial and transcendence in cinema, Dreyer’s Passion of Joan of Arc. Based explicitly on the transcripts, he is grappling with the contradiction of displaying a historic truth as something greater than the sum of its record. Joan’s motive and defence is defiantly metaphysical and defiantly individual, and no less patriotic. She knows what she knows. She will pass over the higher truths that are of no concern to the temporal authority by whom she is tried. She understands the power of the symbols of her struggle, her clothes, her banner, her sword, her king, her voices.

Her judges understand their power as well. Ironically, they agree on the symbols’ power, and only her abjuring of them will save her. As with Man Escaped, we know the outcome even before entering the cinema. Man Escaped by the title, Joan by the history. Drained of this suspense we can focus on the “why”. Here for the first time, the exchange of looks becomes the studied, rhythmic gesture that defines the film’s meaning. We look and are looked at by seen and unseen forces. Finally the cross is held up for her final mortal perception before she disappears and the camera lingers on the empty shackles, all that we are left with. In the drained expressionless, affectless presentation of the story of this story of a recognized saint and martyr we are left with nothing to hold onto but a sense of how she was simply a child elevated by burning to the symbolic power of the same order of power as her voices.

One way of understanding what Bresson was attempting in these rigid performances presented in rhythmic sequences of frames, is by comparison with Japanese Noh. Noh is a ritualized performance whose goal is not naturalism or originality, but a precise re-presenting of deeply understood and felt stories from Japanese tradition. One goes to the theatre not to be entertained or to learn something new or to be transported somewhere else, but to be reassured of exactly what you know, and how you know it. In this way it is not unlike the Catholic Mass, in that a performative enactment is undertaken for the audience that knows exactly how it goes and where it ends and finds comfort in that certainty. Of course in the contemporary west, there is so little we can say that we understand in this way, the challenge is simply to find subjects worthy of the treatment. Joan provided the perfect means for Bresson’s liturgical style.

When an artist like Bresson is so methodical in contradicting the standard practices of his medium and so insistent in defying the expectations of an audience, one has to ask what he is up to? And what he is up to, of course, is getting us to ask “what is he up to?” The strategy may or may not work, I think it remains an open question, at least in part in Bresson’s career, because it demands a second order of attention through the metaviews of scholarly discourse and study. James Joyce gleefully predicted he would keep the academics busy for years. John Lennon was happy to tweak the noses of the “pseuds” as he called those who examined too closely his work, with work that he hoped defied interpretation. Rejecting interpretation and ones place in a tradition is the impossible paradox of shaking something off in the act of using it. Getting dry standing in the water.

Looking at Bresson one is brought to the same kind of theological impasse that occupied James Joyce, the simultaneous embrace and rejection of phenomena as capable of an existence in the world that is devoid of meaning. Somewhere in my reading associated with this Bresson course, I came upon Occasionalism and Nicolas Melebranche, who said “attention is the natural prayer of the soul”. Later in his career Bresson has a character in The Gentle Woman, say: “I want to pray but all I can do is think.”

Albert Einstein: “Try and penetrate with our limited means the secrets of nature and you will find that, behind all the discernible concatenations, there remains something subtle, intangible, and inexplicable. Veneration for this force beyond anything that we can comprehend is my religion.”

Bresson insists on a kind of restful, alert incomprehension. What the Greeks called Ataraxia. Some of us ( those who embrace Bresson ) are comforted by doubt, for others that doubt is cause for distrust and they find Bresson threatening, derisory. This of course, is the same response polarity to Bob Dylan. Nothing is more delicate than “explaining” Bresson. The tightrope he walks is followed by the viewer and anyone wishing to “explain”, to themselves or to others, stands over an uncompromisingly real, void.

Au Hasard Balthazar. In Notes Bresson speaks of images “in contact with other images transforming”. This associational montage is not quite the Eisensteinian synthetic montage. Every image is Bresson is complete in itself and then takes its place in the unfolding. It is fully realized in Au Hasard Balthazar. The donkey is placed in the world with a passivity that is receptive only, there is nothing active in the donkey, it is a vessel. The film, perhaps his most famous, might be his least successful for its sense of it being a moral treatise. The numinous is compromised in the palpable cruelty. A little too “on the nose” and of interest to note recent scholarship that has uncovered a deeply influential children’s band desinee as an apparent source.

It is in Au Hasard Balthazar that a reference to “Action Painting” confirms my earlier observation of the blotter in Diary. The film is redeemed in its final frames as the dying donkey is surrounded by sheep — the kind of image that comes to one in a dream.

One of things that keeps people returning to Bresson’s meagre dozen films is that they are the most obvious to experience and the least obvious to explain. Not to say that it is a thrilling encounter, quite the opposite obviously. But it is impossible to leave without a sense that one has been in the presence of mystery. If one arrives with openness and goodwill — and it uniquely demands a shedding of all our pent-up cynicism if we are to be at all receptive — then one leaves each time more curious than the first.

Les Dames de Bois de Boulogne. Up, down and sideways. The film is a choreography and a study in the vectors of movement as symbolic of compromised spiritual states of desire and revenge that are purified in love. Dancers spin, elevators rise, water rains, cars move laterally, until finally all movement is arrested as Jean is boxed in by Helene’s vengeance seeking and finds in his capture, ultimate release in love. Only his second film, but he is quickly gaining control of the medium to express exactly the human condition that will characterize his life’s work. Cocteau may have written it, but it is Bresson directing.

Mouchette

A bleak meditation on the suffering innocent. Repetition is the key to rhythm and here we have virtuosic rhythm. A dance of eyelines as looks meet, miss and stare. Again, no attempt at naturalism, they are poses in a composition in time. It as extravagance of moments, linear only in the sense that pearls on a string are linear. Anyone can toss off a symbol, artistry is their orchestration. Mouchette is dramatic only in the sense that a folksong to which we all know the words is dramatic. Like poetry, repetition of reading is essential until you know the tune. Mouchette is not a piece to be seen once. It feels like an elaboration on Au Hasard Balthazar. Mouchette is not unlike Agnes in Dames de Bois de Boulogne in that she is a victim who finds no redemption. The rhythmic nature of the piece is underscored by the chaotic moments of mud slinging and shotguns. Like the muling of the donkey, like the firecrackers in the Au Hasard. “Disorder will win out because that is the way of the world” says the old priest in Diary.

Bresson met Chaplin. Chaplin told Bresson that the camera will record the thoughts of the performer. This is a metaphysics shared with the indigenous who fear a piece of their soul goes with the image “taken”. Bresson is a cinema of takes. Performers apparently were asked to repeat the action over and over until it was drained from them. It is almost diabolic. What possesses an artist to believe they have dispensation to invoke the deity? The answer is probably that work not granted that power disappears into time’s oblivion. The work of the artist granted access is the work that endures.

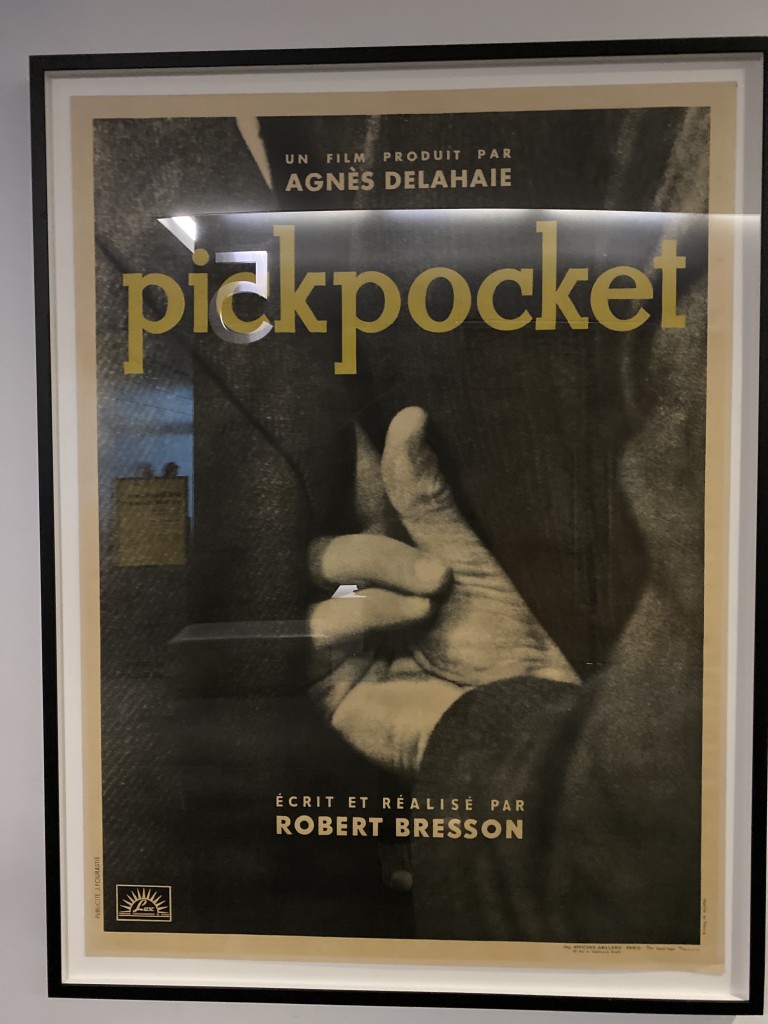

Pickpocket. More letters. The “look”, again, is the fundamental action of the movie. But this time, the look is denied, mitigated, annulled by the act of picking blindly, both for the thief and the victim. Judgement is suspended by the mother, by the cop. He is an artist or philosopher manqué. He drifts in an entirely modern way. Theft is an act of curiosity. Voyeuristic. Erotic. Saint Genet. Where Mouchette was a ballet of eyes, this is a ballet of hands. Here the montage is pure Eisenstein. As Michel is instructed by the veteran thief, we are instructed in the act of viewing. We can proceed untutored or we can accept instruction. Bresson’s is a discourse on cinema in the language of cinema. Again I am reminded of Noh. The performer serves the poetry which has an autonomous and complete existence unto itself. The cinematic image is the primary element in transmitting the poetic essence and must not be confused with the performer who is there only to serve it. As victims we are culpable in the crime against us by our oblivious trust in world’s benignity.

“Colour is light; light belongs to it”

“Cezanne did everything it was possible to do. When I was a painter, I would race to the cinema every night — like many other painters — because that’s where thing were moving: the leaves on the trees —- they moved!”

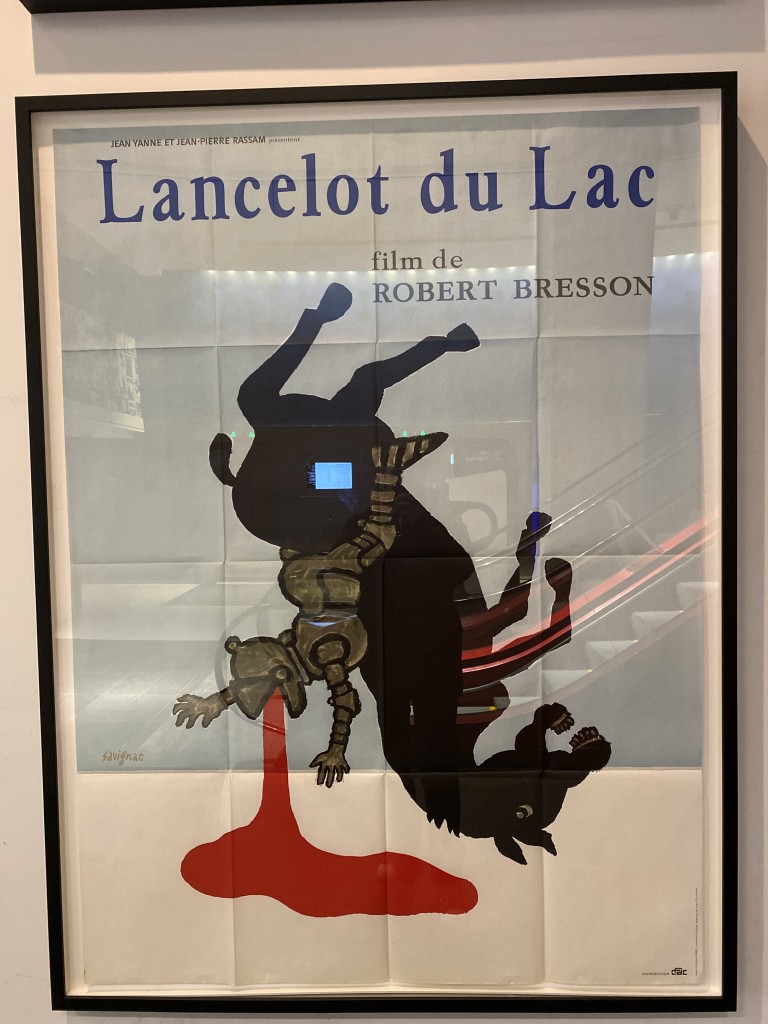

Lancelot du Lac pits the primeval against the technological in his most formalist piece. Joan was historical and the documents were the raw material. It had recourse to a record of fact. Lancelot is fable and the only recourse is to our common knowledge of the folk tale. Meticulous attention to detail and colour in costume, in heraldry, in the silver and sylvan. Blood. Hieratic elements carry the meaning. War is men in metal over and over again spilling blood. The face effaced behind a helmet. Noh uses the mask to the same purpose. He speaks of the importance of improvisation and forgetting every scene the night before he goes onto the set. Manifestly so in Lancelot where one senses he amassed a collection of elements and then gave free rein to allowing the lineaments of the grail story lead him wherever the elements would. It is a palette. It is collage. It is repeated ad nauseam that Bresson’s work is liturgical. I would suggest that it is circus. Who would expect naturalism from jugglers and clowns? We suspend ourselves under the big top. We suspend ourselves in front of Bresson. There is a distinction in painting between ébauche and étude. Colour subverts the traditional prejudice of line over shading, a bias that is reinforced in Black and White. In colour a riot occurs. The modern is graspable directly in colour. Mouchette could have been made 100 years before its date of making. Lancelot is profoundly a work of today about yesterday. With colour Bresson fully enters the modernist tradition where before he was a scholastic. Again to referenc Noh. The Lancelot allows him to engage with a tradition, with a story that was (is) part of the fabric of European culture. The stores are archetypal and so allow him to engage with the “how” of their conveying.

Un Femme Douce is the work of an artist who has witnessed Paris 68. It is the work of a master in complete control of his canvas. Here performance is inflected with enough style to suggest its aesthetic beauty as minimalism and not simply opposition to a more florid expressive mode. Again, all suspense is drained from the flashback form. He collects objects. She collects the numinous. They share a ledger, she on the sell side, he on the buy side. It is a drama of accounting. Their marriage license mirrors the ledger. A relationship governed by the circumstance of time and place. An acknowledgement of emergent feminism.

“But it’s impossible to tell what it is about art that can produce divinity. Art is not a luxury but a vital need”

What he shares with Beckett, Joyce, Pollock is a concern with strategies that interrupt received doctrine about what art must be and how art is made. It is what Benjamin as a Marxist critic is attempting to explicate in his analysis of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. From here on the work takes on a more political shading.

Four Nights of A Dreamer then. The artist with his recorder. It is very much a Benjamin meditation. At this point I was becoming preoccupied with the emerging pandemic. My notes thin out. It is a master work. The observation of the contemporary youth movement which could be caricature is ultimately sensitive and fond to the callow folly, to the naive idealism of collectivity by the banks of the river.

That Four Nights of A Dreamer was also made by Visconti not too long before suggests that Bresson did have an eye on Dreyer, that these are “answer” films.

“Sentimentalism is the enemy of cinema”

Dostoyevsky as an influence is in that anti-sentimentality.

But Four Nights does, too, feel like it is in dialogue with his own work — to the particularly bleak Une Femme Douce.

The Devil Probably

Watched on an ipad screen. These conditions of viewing matter. Where Four Nights ends with the bateau on the Seine passing under the bridge. The Devil Probably opens with the same bateau. It is apparent that many of Bresson’s characters are youth, but it is in these final films that youth becomes a study in itself, if not the singular element of the cinematograph then a central and activating component of the study. Studies, might be the most apt synonym for the thing he called cinematograph. Although they contain elements of other arts, they are more than moving photographs, more than drama, more than spiritual meditation, they are probably closest to the Montaigne Essai.

L’Argent.

The ouevre as entity. The mutuality of viewing the latter films through the lens of the former, but given the necessity of multiple viewing, the viewing of the former in the retrospect of the latter. There is an inevitablility to the work that suggests it all came of a piece. Itis a string of pearls. Like poetry it doesn’t have to cohere as linear narrative, but threaded images apprehended as an entity. A retrospective of the work of a Bresson is the Collected Works of a poet.